After my junior year of college, I had a summer internship at what was, unbeknownst to me at the time, one of the last PM daily papers in the United States, the Phoenix Gazette. The Gazette was down to about 1/10 of the circulation of its morning rival, The Arizona Republic – both were owned by the same company but maintained separate staff – but was hanging on. Given the trends underscored by the latest report from comScore, Digital Omnivores, we may be in a window where people one day will say they were at one of the last newspaper organizations NOT to have an online PM strategy.

For those of you too young to remember, a brief summary of the relevant history: A little more than a generation ago, more newspapers were sold in the afternoon than the morning, and many cities had both a morning-delivered paper and an afternoon-delivered paper, the latter of which originally was dominant. As lifestyles changed, the afternoon paper faded and the morning paper became dominant, and by the ‘80s few PM papers were left. Whatever news had happened in the wee hours overnight, people heard on the radio or TV in the morning, and whatever happened during the day, people heard on the radio on the drive home or on TV shortly after arriving home. In recent years (as many have observed) the Internet is accelerating the adaptation of news-consumption habits to peoples’ lifestyles and schedules – so much so, it seems, that there now is renewed and growing demand for a late update on the news, but later than the old PM paper and later than the evening TV news.

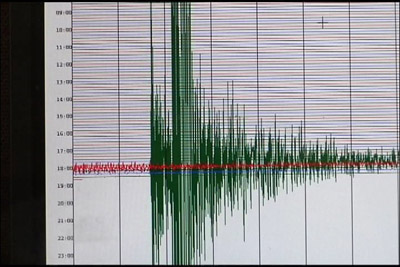

One of the highlighted elements of the comScore report is the rapid growth in mobile and especially tablet use. This is important because, as the chart shown above illustrates, when people use their computers to check online news, the pattern rises and falls according to the day’s work schedule – peaking in the mid- to late morning and declining late in the day. But mobile use hangs on later – especially tablets, which actually peak later in the night.

A danger of drawing too many conclusions about where the trend goes from here is that the current batch of tablet users are mostly young, male and affluent – not the typical computer user, let alone mobile user, let alone the average person. But they are typical of early adopters, and to that extent, you can look at their usage with an eye to what past early adoptive behaviors indicated was the shape of things to come.

For news producers, the news is hopeful:

News is relatively high on the list of what people do on mobile devices. True, it’s below e-mail … Facebook … games … Google and Yelp and other search … maps … . But still, it’s a solid third or more of the market.

Not only that, but it’s among the higher percentage of uses in a month, especially among tablet owners (and the report emphasizes the growth and potential of the tablet audience):

“Nearly 3 out of 5 tablet owners consume news on their tablets. 58 percent of tablet owners consumed world, national or local news on their devices, with 1 in 4 consuming this content on a near-daily basis on their tablets.”

(Note: Among tablet owners, “TV remained the most prominent source for news content, with 52 percent of respondents typically consuming news in this fashion. Computer use followed closely with 48 percent of tablet owners consuming news content via desktop or laptop computers, while 28 percent reported receiving their news from print publications. Mobile and tablet consumption of news were nearly equal in audience penetration, with 22 and 21 percent of respondents accessing news via their mobile or tablet devices.”)

And finally, a word of hope for the news organizations formally known as newspapers (yeah, I’m a few years ahead of myself, but that’s where we’re going): Newspapers, blogs and technology sites stand out as examples of categories in the U.S. exhibiting high relative mobile (phone and tablet) traffic.

“In August 2011, 7.7 percent of total traffic going to Newspaper sites came from mobile devices – 3.3-percentage points higher than the amount of mobile traffic going to the total Internet. As consumers continue to seek out breaking news and updated information on the go, it is likely that this share of traffic could grow further.”

In summary: It’s early, but this is another data point backing up indications that the trend is that at least a significant portion of the people using mobile devices (notably including the portion most likely to appeal to advertisers, or with the income to pay for access) have an appetite for news that extends late into the evening, and they go online to find it. When do you do your final online updates for the day?